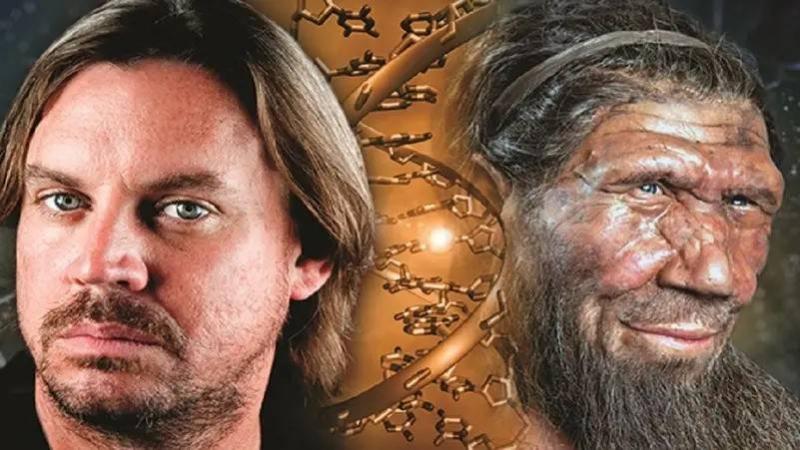

Between 47,000 and 60,000 years ago, there was interbreeding between primitive Neanderthal humans and modern humans that lasted for 6,800 to 7,000 years. During this time, modern humans acquired 1 to 2% of the Neanderthal DNA from those who lived in Europe, the Mediterranean, and Central Asia approximately 200,000 to 24,000 years ago. The "Neanderthal," from which scientists derived the name based on fossils discovered in 1856 in the Neander Valley in Germany, was described as short and robust, with a relatively large skull. This description comes from a study reported by international media outlets, including the British journal Nature and the American magazine Newsweek, where most experts believe that the famous primitive species went extinct about 40,000 years ago.

The causes of its extinction include several factors such as climate change, interactions with humans, and unfamiliar diseases or viruses, notably the adenovirus, known in Arabic as "adeno-virus infection," along with the herpes virus and the human papillomavirus (HPV), which affects the skin and mucous membranes of humans and many animals. The interbreeding was largely one-directional, with limited evidence of modern human DNA entering Neanderthal genomes, which has impacted genetic and phenotypic diversity in contemporary humans. Portions of Neanderthal origin have been identified across more than 300 genomes, supporting a model of a major genetic flow, accompanied by natural selection for positive and negative traits shortly after the gene flow occurred.

The study, written in collaboration with Alchemiq, a company specializing in generative artificial intelligence news, confirms that not all populations have the same amount of Neanderthal DNA, with Africans having the lowest percentage. Despite this, the majority of individuals globally possess about 2% Neanderthal DNA, according to the study, which indicates that all humans have a percentage of Neanderthal DNA that can influence various aspects of health.