Projects for COVID-19 vaccination using patches have been increasing since the onset of the pandemic, marking a potential revolution in the way vaccines are administered in the future. According to Agence France-Presse, this technique may help avoid crying crises during injections in children, and it has other significant benefits, including enhanced effectiveness and better dissemination. A study conducted on mice and recently published in the journal "Science Advances" revealed promising results.

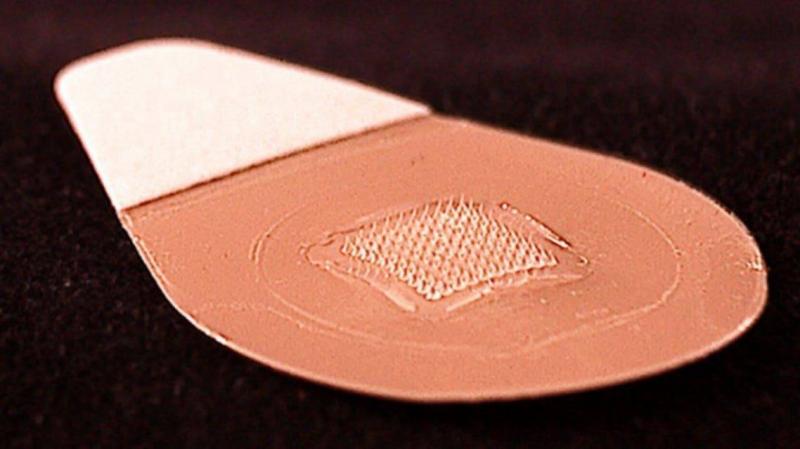

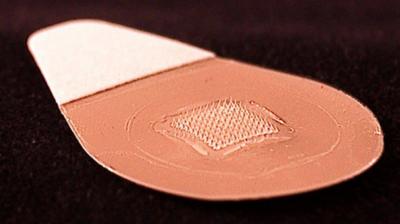

The study centered around a plastic square patch measuring one centimeter in length and width, featuring over 5,000 tiny pointed heads "small enough to be invisible," as stated by epidemiologist David Muller, who participated in the research conducted by the University of Queensland in Australia. These heads were coated with a vaccine that penetrates the skin upon application of the patch. The scientists used a vaccine that does not contain the complete virus, but rather one of its specific proteins known as spike proteins. Mice were vaccinated using patches (which were applied to their skin for two minutes) and with needles.

In the first case, a strong antibody response was obtained, including in the lung area, which is essential for combating COVID-19. Muller noted that "the results far surpassed those achieved with injections." In a subsequent phase, the effectiveness of a single dose administered via the patch was evaluated. With the use of an immune-boosting agent, the mice did not contract the disease at all. Vaccines are typically given via injection into the muscles; however, muscles do not store large amounts of immune cells for an effective response as skin does, according to Muller.

Additionally, the pointed heads cause minor injuries that alert the body to a problem and subsequently stimulate an immune response. For the scientist, the benefits of this technique are clear, including that the vaccine can remain stable for a month at an average temperature of 25 degrees Celsius and for a week at 40 degrees, compared to just a few hours for the "Pfizer" and "Moderna" vaccines, thereby reducing reliance on a cold chain, which is challenging for developing countries. Moreover, the application of patches is very easy and does not require trained staff.

The patch used in the study was produced by the Australian company "Vaxas," which is the most advanced in this field. Phase one trials are expected to commence in April.