Researchers have successfully identified the reasons behind the low response rate to the chemotherapy drug "Decitabine" in patients with blood cancer and myelodysplastic syndrome, reviving hope for the development of more tailored treatment strategies. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in the United States, scientists identified the genetic and molecular mechanisms within cells that render the chemotherapy drug "Decitabine" effective for some patients but not others.

According to the study, the chemotherapy drug "Decitabine" works by modifying DNA, which in turn activates genes that prevent cancer cells from growing and reproducing. However, the response rate to "Decitabine" is relatively low, with improvement observed in only 30-35% of patients, leaving some ambiguity about why it fails in certain cases. To understand this, researchers from the Korean Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) investigated the molecular mediators involved in regulating the drug's effects.

How does "Decitabine" work?

To understand the mechanism of the chemotherapy drug, the study indicates that "Decitabine" activates the production of endogenous retroviruses (viral elements derived from retroviruses that are abundant in vertebrate genomes), which trigger an immune response. These viruses had long ago integrated inactive copies of themselves into the human genome, and "Decitabine" "reactivates" these viral elements, producing double-stranded RNA that the immune system recognizes as foreign.

Co-author of the study, Yousik Kim, a professor in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at KAIST, stated that they studied the mechanisms involved in this process, "especially how to regulate the production and transport of RNA molecules within the cell."

Significant Findings

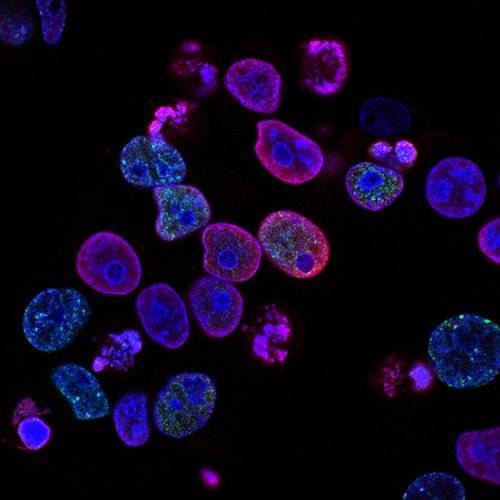

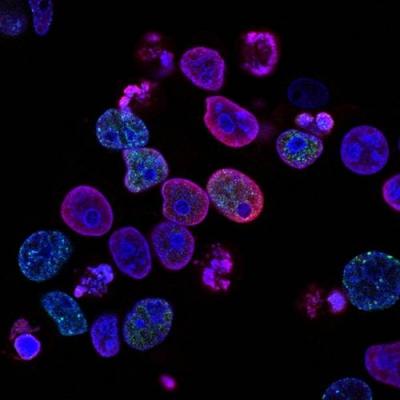

The researchers used image-based RNA interference assays, through which they discovered that two types of proteins play a key role in the drug's response, one called "Staufen1" and the other "TINCR." The researchers confirmed that their study showed that patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia, who had low levels of Staufen1 and TINCR, did not benefit from treatment with Decitabine.

The study's lead author, Youngsook Ko, noted, "We can now isolate patients who will not benefit from the treatment and direct them to a different type of therapy. This is an important step toward developing a personalized cancer treatment strategy."

Given that the researchers used patient samples taken from bone marrow, the next step will be to develop a testing method that can identify the issue using only blood samples, which are easier to obtain from patients. The team plans to investigate the possibility of expanding the analysis to include patients with solid tumors in addition to those with blood cancer.