A new study led by researchers from the University of California has reached the conclusion that a group of genes essential for building our cellular components may also influence human lifespan. Previous studies have shown that genes can extend the lifespan of small organisms, such as increasing fruit flies' lifespan by 10%, but this is the first time scientists have demonstrated a link in humans, as reported in a new research paper.

The co-lead author of the study, Dr. Nazif Alik from the Institute of Healthy Aging at University College London, stated: "We have already seen from intensive previous research that inhibiting certain genes involved in making proteins in our cells can extend the lifespan of model organisms like yeast, worms, and flies. However, it has been noted that the loss of function of these genes in humans causes diseases, such as developmental disorders known as ribosomopathies."

He added, "Here, we found that inhibiting these genes may also lead to increased longevity in individuals, possibly because they are more beneficial earlier in life before they cause problems later on." The genes are involved in the protein synthesis machinery of our cells, which is essential for life, but the researchers suggest that we might not need as much of their influence later in life. These genes appear to be an example of phenotypic pleiotropy (a hypothesis that provides an evolutionary explanation for aging: the control of one gene over multiple phenotypic traits in an organism).

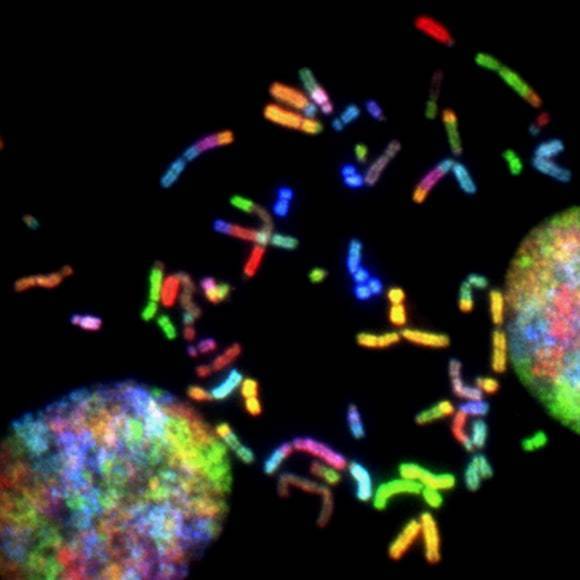

The researchers reviewed genetic data from previous studies that included 11,262 individuals who lived exceptionally long lives into their nineties compared to their peers. They found that those with reduced activity of certain genes were more likely to lead very long lives. The genes are linked to two types of RNA polymerase enzymes (Pols), which transcribe ribosomal RNA and transfer ribonucleic acid, namely Pol I and Pol III, along with the expression of ribosomal protein genes.

The researchers found evidence that the effects of the genes are related to their expression in specific organs, including abdominal fat, liver, and skeletal muscles, but they also discovered that the impact on longevity extended beyond mere associations with any specific age-related diseases. The findings add to the evidence that drugs like rapamycin, an immunosuppressant that inhibits Pol III, might be beneficial in promoting healthy aging.

Professor Caroline Kuchenbecker from the Genetics Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, remarked, "Aging research in model organisms, like flies, and in humans, often remains a separate effort. Here, we are trying to change that. In flies, we can experimentally manipulate aging genes and investigate the mechanisms. But ultimately, we want to understand how aging works in humans. Combining the two fields together using methods like Mendelian Randomization has the potential to overcome the limitations of both domains."