Fahema cried a lot when her husband told her he would sell their two young daughters to prevent the family from starving after they were displaced by drought to western Afghanistan. The two girls, six-year-old Farishta and one-and-a-half-year-old Shakria, are smiling near their mother in their mud home covered with a patched tarpaulin, with their clothes and faces stained with dirt. They do not realize that they have recently been sold to the families of two young boys who will become their husbands in the future. The two families offered about $3,350 for the eldest girl and $2,800 for her sister. Once the payments are completed—which could take years—the girls will have to say goodbye to their family and the displacement camp in Qala-i-Naw, the capital of Badghis province, where their family has sought refuge from a neighboring province.

This story is quite ordinary for thousands of families largely displaced due to drought in one of the poorest areas of the country. In the displacement camp and towns, journalists from Agence France-Presse met around 15 families forced to survive by selling their young daughters for amounts ranging from $550 to nearly $4,000. This practice is widespread. Camp and town representatives count dozens of cases since the drought struck the area in 2018, with numbers rising with the recent drought wave this year.

Sabira, a 25-year-old neighbor of Fahema, took groceries on credit. The shop owner threatened to "imprison" family members if they did not repay their debts. To pay off what they owed, the family sold their three-year-old daughter Zakira to be married to Dhobi Allah, the shopkeeper's son. The child's future father-in-law decided to wait until she grows up to take her. Sabira said, "I'm not happy that I did this, but we have nothing to drink or eat (...) If this situation continues, we will also have to sell our three-month-old daughter."

Another neighbor, Gul Bibi, confirmed that she sold her daughter Ashu, aged eight or nine, to a 23-year-old man to whom she was indebted. The man is currently in Iran, and Gul Bibi fears the day he will come to take Ashu. She said, "We know this is not good... but we have no choice."

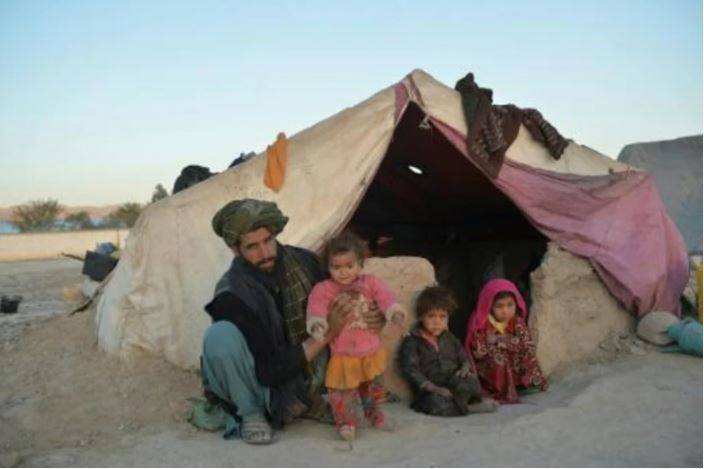

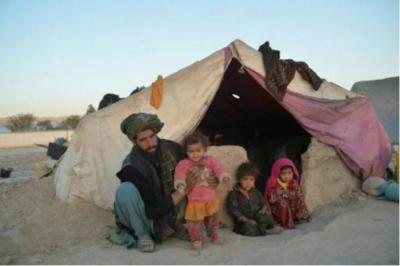

In another camp in the Qala-i-Naw area, Muhammad Asan wipes his tears while showing pictures of his daughters Sana (9 years) and Idai Gul (6 years), who went to their husbands' homes, still far away. He says, "We haven't seen them since... We didn't want to do this, but we had to feed our other children." Trying to comfort himself, he adds, "My daughters are in a better place there, surely, with food," showing the bread crumbs his neighbors gave him, which is the only meal he has for that day. Muhammad, who also needs to pay for his sick wife's medical care, is still in debt. A few days ago, he started searching for a buyer for his four-year-old daughter.

His wife, Dada Gul, sitting under a torn tent, narrates, "Some days, I go crazy, I leave the tent and don't even remember where I've gone." The suffering does not end for mothers: the decision to sell a daughter, then waiting to say goodbye, which often stretches over years until the girls are 10 or 12, and then the separation. Rabia, a 43-year-old widow also displaced by drought, does everything she can to postpone the dreadful day. Her 12-year-old daughter Habiba, sold for about $550, was supposed to leave a month ago, but Rabia begged the family of her future husband to wait another year. The teenager softly says, with a sad look in her eyes, "I want to stay with my mother." Rabia asserts that "if she had food and drink," she would repurchase her daughter. But her three children and she barely have enough to survive. Her 11-year-old son works at a bakery for fifty cents a day, while her nine-year-old son collects rubbish for thirty cents.

Rabia says, "My heart is broken... but I had to save my sons." In the camps, displaced people eat food that costs just a few cents a day, earned by begging or pushing a cart. They wonder how they will survive with the onset of winter.

Every evening, Abdul Rahim collects bread to help the poorest families. Regarding child marriages, he states, "I have seen about a hundred families doing this in this camp. Even my brother." The day before, he met with Taliban officials to ask for help. However, they are powerless in a province where 90% of residents are at risk of food shortages.

Malawi Abdul Sattar, the acting governor of Badghis province, told Agence France-Presse that these marriages "result from economic problems, not a rule imposed by" the Taliban. The legal minimum age for girls' marriage was 16 under the previous government before the Taliban's takeover in August. According to a report by UNICEF in 2018, 42% of Afghan families have a daughter married before reaching 18 years of age. This is primarily due to financial reasons, as marriage is often seen as a way to secure a family's survival. However, girls married early face significant risks ranging from complicated childbirth to domestic violence or abuse.

For the husbands, buying a girl is cheaper than proposing to a young woman. The issue has also spread to displacement camps in Herat, Afghanistan's third-largest city, located further south. Allahuddin, a displaced person in Herat originally from Badghis, recounts that he sold his 10-year-old daughter. He says, "I would never have done this if I had a choice." He has another girl aged five, and asserts that if he could, "he would sell her too."

Behind such stark words, parents live with profound suffering. The expressions of their voices and eyes embody their endless despair at their inability to meet their families' needs. Former farmer Baz Mohammad from Badghis states, "I know this is not good... but I thought we would all die."