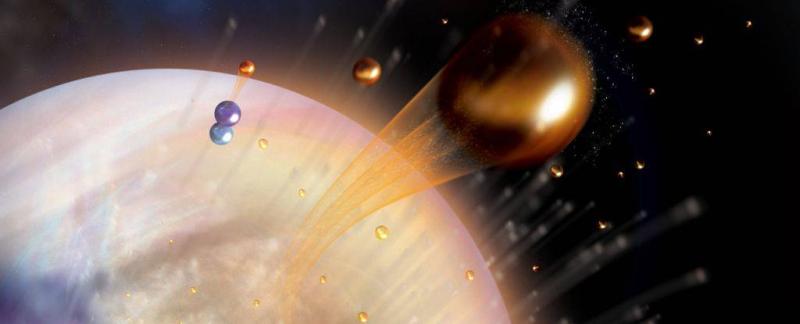

American planetary scientists have found that "most of the original water reserves on Venus have evaporated into space due to interactions between ions and free electrons in its upper atmosphere." The press service of the University of Colorado reported that the search for these ions should be one of the main tasks for upcoming space missions to Venus.

Michael Chafin, a researcher at the University of California, explained: "Currently, there is 100,000 times less water on Venus than on Earth, despite the similarities in size, mass, and origin. If our theory is correct, there should be a large number of HCO+ ions in Venus's atmosphere." He added that this is linked to the rapid evaporation of water from Venus into space.

The scientists reached this conclusion while studying the chemical reactions involving water that occur in the atmosphere of Venus, which is composed of 96% carbon dioxide and a small amount of nitrogen. In addition to these gases, there are also other substances in the atmosphere, including water, carbon monoxide, hydrogen, deuterium, and various sulfur compounds.

As planetary scientists clarified, their interest in studying the reactions in Venus's atmosphere arises from the fact that current theories cannot explain the very low concentration of water and the significant excess of deuterium, a heavy isotope of hydrogen, in the atmosphere of the solar system's second planet. Guided by this idea, the scientists developed a computer model of the upper and lower layers of Venus's atmosphere and monitored the interactions and migration of molecules within it.

These calculations showed that the HCO+ ions produced by the reactions between water and carbon dioxide in the lower layers of Venus’s atmosphere play an important role in the evaporation of water from Venus. HCO+ ions are highly unstable because they easily decompose into carbon monoxide and hydrogen when reacting with free electrons present in Venus’s upper atmosphere. The resulting atomic hydrogen escapes easily into space, a factor that astronomers had not considered in the past, as no previous spacecraft sent to Venus had detected HCO+ ions in its atmosphere. Scientists hope that future missions to Venus will not suffer from this drawback, allowing them to test this theory and estimate the former and current rates of hydrogen escape from Venus's atmosphere.