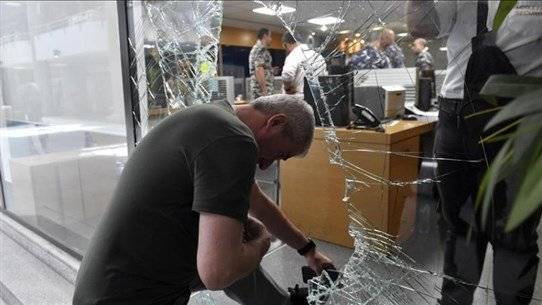

Last Friday witnessed a predicted escalation in the deadlock between banks and depositors. The day of invasions led to some "invading" depositors obtaining part of their deposits, while others left empty-handed. How does the law explain what happened, and where do things go from here?

On Friday night, the Attorney General, Judge Ghassan Oueidat, issued a judicial mandate to all security agencies to pursue criminal acts committed within banks and to work on arresting the perpetrators and instigators, referring them to him, as well as uncovering the connections between these acts, considering them armed robbery aimed at halting banking operations and creating further crises. This mandate was deliberately leaked to the National News Agency, while the General Prosecutor conveyed its contents to the Central Security Council to discuss the necessary measures to be taken.

Let us recall a little back. On March 10, 2020, several public prosecutors met in the office of the Attorney General with a delegation from the Banks Association led by its president, Salim Sfeir, in the absence of any depositors. This meeting resulted in an agreement record, knowing that the role of public prosecutors is to open investigation records with the perpetrators, not to draft an agreement. The title of the meeting was "Finding a Solution to Protect Depositors and Ensure the Safety of the Banking Sector," and it is also noted that regulating the relationship between banks and depositors is not within the jurisdiction of the Public Prosecution in any case. Subsequently, circulars and procedures were issued in favor of banks and their association via the Governor of the Central Bank of Lebanon, which are entirely illegal according to several issued judicial rulings. Here we understand the reasons behind the insistence and desire to enact a retroactive capital control law, covering the legal chaos practiced by banks against depositors.

This meeting preceded the issuance of a directive from the Financial Public Prosecutor on March 5, 2020, based on a complaint related to transfers made by some influential individuals abroad, prohibiting 20 local banks and their board members from handling their funds, commissioning the concerned departments to implement the directive's contents. That day, however, the Attorney General froze the effects of that directive, claiming that the public interest required it. Another cover for the arbitrary banking practices.

The mandate we are discussing comes two and a half years after the above-mentioned agreement. What exactly did Oueidat imply in his mandate? Are the instigators the lawyers representing depositors? And does the term "armed robbery" legally apply to the cases we have recently witnessed in banks?

A known response? One of the legal representatives of Abdullah Al-Saai—the first depositor who invaded the Bank of Beirut and Arab Countries in December—who managed to obtain his deposit of $50,000, attorney Wasef Al-Hareh says to "Nidaa Al-Watan": “Judge Oueidat talks about the existence of instigators as if he is oblivious to the country's problems. People do not need instigation; they are defending themselves. The real crime is what the authorities have done by stealing the country and the deposits of the people.” It is natural for a person to engage in “justifiable self-defense.” It's obvious that one must take their rights into their own hands in a country where many judges obey politicians who themselves are bank owners or partners. If there were active judicial accountability from the beginning against those who squandered deposits, the scene of invasions would not have repeated, according to Al-Hareh, who adds: “What is required from a people searching for their livelihood? If they don't care about us, we will not allow a person stuffed with theory to lecture the starving on patience. It is unacceptable to leave the perpetrator free and dictate to the victim’s family how to mourn.”

When we ask about the background of the judicial mandate, he replies: “Bank owners and the Central Bank Governor and politicians have provided many services to judges through appointments and hiring; the appropriate time has come for them to reciprocate. This is, simply put, the size of the issue.” Abdullah Al-Saai's case was closed after the bank complied and signed a waiver of the lawsuit. As for the decision to close banks for three days (starting today) and its implications, Al-Hareh considers it one of the tools the system uses to extort people: either submit to the status quo or break the will of the people. “Let’s assume banks were attacked; can they tell us why no one moved when it attacked people’s deposits?” Al-Hareh concludes, emphasizing his commitment alongside his colleagues to support the people regardless of the cost, even if labeled instigators.

The Moment Everything Explodes

We move to Ali Abbas, the attorney for Sally Hafiz and her detained companions, Mohammed Rustom and Abdul Rahman Zakaria. For Abbas, what is happening in banks is the result of accumulations in the absence of a law regulating the relationship between depositors and banks. "There is no equality among depositors; influential people are able to smuggle their money while others are subjected to illegal haircuts, noting that all circulars issued lack legal basis." This is seen as a source of tension, according to him, compounded by the absence or silence of decisive judiciary action, which has a role to play in this regard.

But why the explosion now? “Depositors have no choice but this method, especially after the judges’ strike. There is always a moment that explodes everything when the cup overflows. Also, September is the month of living obligations. Sometimes citizens lack the courage, but public opinion and media sympathy for Sally, combined with the revolutionary spirit she brought into the bank, motivated others to follow suit,” Abbas believes.

Regarding the mention of instigators and the connection of the actions, Abbas says: "What is happening is not a crime but a confrontation with the crime of the century. What we have witnessed was expected due to the arrogance of banks. But can Judge Oueidat tell us what connects a first lieutenant in the army with a depositor from the Tarik Jadideh area? The talk about incitement and the connection of events is illogical, and a police state cannot be established over a people that has nothing left to lose.”

About the reasons for not detaining Sally until now, Abbas noted that she chose to remain hidden, considering her actions do not constitute a crime requiring her to surrender. This is her choice, and a legal strategy is being developed to confront the search and investigation warrant against her. As for her detained companions, “We learned that if Sally turns herself in, they will be released, but it later became clear this was an attempt to ‘drag’ everyone. We do not accept blackmail, and the two detainees have not committed any crime according to video recordings. There is no justification for their detention, nor do we want them to be scapegoats,” he asserts.

There are two options, as he says. Either they will be released after surpassing the preventive detention period or be referred to investigation through a detention order. However, Abbas anticipates their transfer to the first investigative judge for their release instead of Judge Oueidat, as the latter has become embarrassed by the outcome of the mandate he issued. He concludes: “We will not accept the use of judges affiliated with the system to continue the latter's agenda that crushed the people in exchange for keeping positions.”

Behind the Mandate

Returning to the judicial mandate and its legal interpretations. The coordinator of the legal committee at the Popular Observatory against Corruption, attorney Jad Taame, noted in a statement to “Nidaa Al-Watan” that the mandate entrenches the reality of protection that the Public Prosecution has provided to the Banks Association and board members under the pretext of public interest since the beginning of the crisis. "It does not include any consideration or understanding of the suffering of depositors who have faced the harshest forms of humiliation by the banking sector for two and a half years. It also did not consider the crimes committed by banks against depositors, at least when they stole their deposits and compensated them with a trivial amount per dollar deposited in the account, far removed from reality under the policy of account ‘haircut,’” Taame expressed.

The ongoing chaos serves the interests of two parties: the banking sector, which has accumulated profits during the crisis at the expense of people's suffering, and the state, which has reduced public debt by playing on exchange rate differentials. All proposed economic recovery plans from the state or economic bodies or banks come at the expense of people's deposits. Moreover, it has become clear that the depositors who invaded banks have deposits that do not exceed $200,000 at most; therefore, these individuals cannot pose a danger to other depositors as the Interior Minister implied to incite depositors and place them face-to-face. “The real danger that requires alerts from ministers and judges lies in revealing the identity of those who smuggled millions of dollars, the hidden details of investment in Eurobond purchases, who decided not to pay their value at maturity, who caused the crisis, and exploited it to achieve astronomical profits at the expense of public funds first and depositors second. It seems that the Public Prosecution needs a wake-up call to appreciate who the criminal is—raiding people's funds—and who enters banks after being cornered by a lack of means to secure a living in the wake of the judiciary’s retreat and failure to achieve justice. Where should the harmed depositor turn?” Taame wonders.

When we inquire whether the invasions fall under the term “armed robbery” as mentioned in the mandate, Taame clarifies that "the legal classification of what occurs with depositors is, in fact, ‘self-reclamation of rights.’ As for the armed robbery issue, it is subject to many discussions, especially since this presupposes the presence of real weapons, while it clearly appears that the weapons used are generally fake." The Public Prosecution seems to be trying to imply that there is a felony being committed here, intimidating people and deterring them from continuing down this path, forgetting the implications of the judicial withdrawal and the legal rulings related to states of necessity and justifiable self-defense.

For Necessity's Sake

What is the fate of this confrontation? "We certainly cannot encourage the continued self-reclamation of rights, and we hope that depositors are not pushed to repeat these scenes. However, this requires establishing a logical, consensual legal framework that protects people's rights and allows them to recover their deposits at their true value and in the currency of their deposit." Taame reminds whoever speaks about crimes committed by depositors, whatever their type or description, that we also face banking procedures that fit the criminal description and which are still not pursued by public prosecutors under the argument of preserving the banking sector, which the Public Prosecution classifies as a public interest. The latter must make its choice after more than two years into the crisis and the judicial grace period for banks: either prosecute the people who will act to recover their deposits or force banks to retract their arbitrary actions and come up with a just solution that does not violate depositors’ rights.

And while he noted that self-reclaiming rights cannot lead to a decision to return the depositor's deposit since he did not steal money but rather obtained his right, Taame concluded: “Let us remember that the relationship between banks and depositors is governed by a contract. Legally, a contract is considered the law of the contracting parties, and what two wills agree upon cannot be changed by a single will. The banks' failure is, in no way, a reason to impose on the depositor the reality of not recovering their deposit, especially since the crisis is caused by the decisions of bank boards to invest funds in abhorrent debts, meaning high-risk debts.”