On the night of February 14, residents of the western Beirut suburb noticed unusual security measures, where armed members of Hezbollah set up checkpoints on main roads and side intersections. People initially assumed these measures were related to the ongoing confrontation with Israel, but it later became clear they were due to the visit of Iranian Revolutionary Guard Commander Ismail Qaani to Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah. Various sources, some close to the party, reported that the meeting lasted three hours and was attended by Hashem Safi al-Din and one of Nasrallah's sons. It was said that Qaani conveyed instructions from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei for restraint and to avoid escalation in the war with Israel, even if the rules changed and they encroached into Lebanese territory provocatively, causing destruction and killings. Iran does not wish to expand the war to a comprehensive scale, understanding that, aside from the exaggerated media support, the war would be devastating for its most important ally, Hezbollah, which has invested significantly to gain control over Lebanon and parts of Syria.

A sense of dissatisfaction and frustration has leaked from within the party, and some media outlets aligned with Hezbollah began to claim that the party would face the situation alone, using new terms like those coined by Khamenei such as strategic patience alongside insight. After Nasrallah had boldly spoken of deterrence power and destruction capabilities beyond Haifa, he urged weeks ago against using mobile phones to prevent Israeli eavesdropping on Hezbollah's movements.

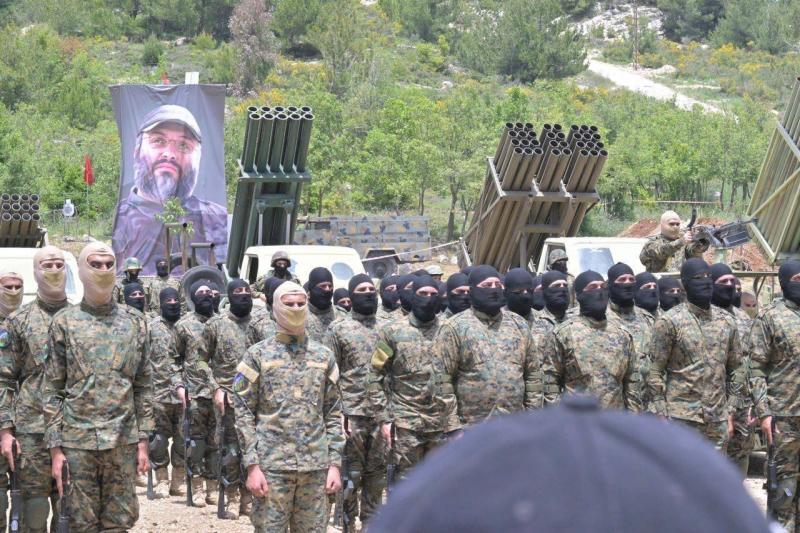

This was followed by a "celebration" organized by Hezbollah for the resistance axis militias in Beirut, where the Houthis committed to continue their attacks from Yemen to disrupt global trade under the pretext of defending Gaza. Hezbollah confirmed its continued destructive policy for Lebanon, aiming for it to become identical to Gaza.

The Lebanese situation exemplifies Iran's strategy of maneuvering, confronting, and negotiating through arms that have been deeply invested to enable control over states, which then act at the behest of the Iranian regime in service of its interests, regardless if this is against the interests of those nations and their peoples. The last time Iran faced a direct confrontation was when the former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein challenged its export of revolution during a bloody war against it in 1980, which lasted eight years, and they had no option but to engage.

Iran has no desire for direct confrontation with the West, especially the United States. What it aspires to is to convince the Americans of its control and influence, which allows it a pivotal role in stability—or instability—and therefore, it hopes for the lifting of the suffocating American sanctions and the release of funds that remain largely frozen in global banks. The Iranian regime's problem is that Americans do not highly value Iranian control over countries that, thanks to Iran, have become failed states plagued by poverty and deprivation. The U.S. bets on time, which will eventually erode Iran's control over these nations, similar to what Russia experienced with the loss of its dominion over the former Soviet republics.

Meanwhile, UN Security Council members strongly condemned the Houthis/Iran attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea last Monday. Iran is relying on the Houthis' challenge and their continued attacks on ships even after a series of recent strikes by the United States and the United Kingdom targeting missile launchers in Yemen.

At the same time, analysts are closely watching what could result from this. It is suspected that two Iranian ships, Behesht and Safiz, are providing intelligence to the Houthis, aiding in attacks against commercial and American vessels in the Red Sea. Just two days after the U.S. attacks against Iranian proxies on February 2, Iran issued a stern warning against attacking ships.

So, with the Houthis continuing their attacks in the Red Sea, what may happen? A Western security source justifies saying: it’s easy to say the U.S. should strike all Iranian capabilities in the region, including its proxies and sites. The U.S. wishes to be cautious about turning the Arabian Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Gulf of Oman—vast water bodies—into an area less conducive to secure trade and transport.

My interlocutor believes that for the United States, the goal would be to strike Iran’s militias in the region and eliminate some of their leaders, then observe how this message spreads throughout the region. On the other hand, there are American weapons in the area; in addition to the B-1 bombers, the U.S. has nuclear submarines and highly advanced vessels with capabilities that Iran and its proxies have no defenses or ability to counter. All this itself sends clear and explicit messages to Iran and messages to the U.S. partners in the region. Iran is still far from receiving strikes, and its proxies will see that it cannot do much to protect them.

Global shipping has certainly been affected. There is no real indication in the near term that business will return to normal in the Red Sea. Regarding shipping issues, there has been much discussion about what this means in terms of additional costs, the impact on energy in some containers, and inflationary pressures on some governments. The situation in the Red Sea will remain tense for several reasons. Although the number, frequency, and intensity of Houthi attacks in the Red Sea have diminished and will continue to decrease with the United States destroying closer capabilities to the Red Sea, this water body is one that no one will want to test with expensive container ships until they know it will be secure. The Houthis are likely to exploit this and use anti-ship weapons as long as they continue to transit.

Emerging and developing countries are certainly taking this situation seriously. There are more than 40 nations with interests or stakes in the vessels that have been targeted so far. Some countries have suffered greatly, watching essential commodities like iron ore and various goods delayed or disrupted, as well as textile deliveries to the United States. These countries lack the easy ability to move goods back and forth and tolerate disruptions in their supply chains and economies. Thus, inflationary pressures that the West can absorb may hit the economies of these nations, as well as deflationary issues, recession problems, and energy prices that are much harder for emerging and developing countries.

In some cases, this is an opportunity for investments, but it is also a concern for policymakers. The question that can be posed to those wanting to divert attention from the shipping issue will not be what will happen when the Houthis stop, but rather what is the plan to push Iran to retreat? Because it will continuously seek to disrupt any attempts, having gained global influence with its proxies. From here, we understand Washington's request for indirect negotiations with Iran in Oman to restrain the Houthis; even the U.S. has not been spared from the costly effects of Houthi strikes, as the American supply chain was disrupted, forcing trucking industries to move to the West Coast from the East Coast, making the frame of damage very broad.

It is worth noting that an official from the "Ansar Allah" group emphasized last Monday the continuation of its operations against the Israeli occupation's interests even if humanitarian aid enters the besieged Gaza Strip!