Evidence of human habitation dating back between 452,000 and 165,000 years was found in a cave in the central Iranian plateau, including carved stone tools, horse bones, and primary (milk) teeth, which are the oldest ever discovered in this vast region. A study published at the end of May in the "Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology" indicates that this finding means the first dated evidence of settlement in the area is now 300,000 years older than previously thought. Researcher Gilles Périon from the French National Center for Scientific Research at the Museum of Man, who participated in the study, explained that such ancient archaeological materials are rare in this area.

Prehistoric scientists knew that the central Iranian plateau had been inhabited for hundreds of thousands of years due to multiple sites in the surrounding areas—like the Arab East and the Caucasus in the west, and Central Asia in the east—where humans from various species lived. Additionally, a series of discoveries of carved stones in Iran, some above ground and others uncovered in rare excavations in specific locations, provided evidence of human presence. However, no excavation had yet allowed for such a precise chronological sequence over such a wide range.

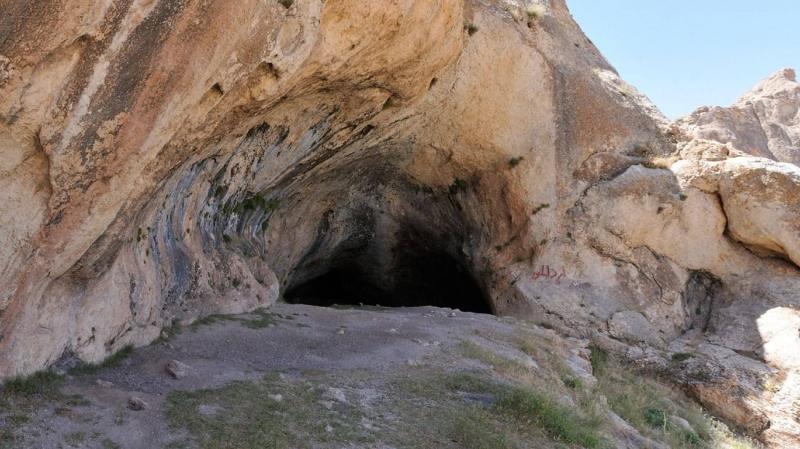

In 2018, a French-Iranian anthropological project team led by Gilles Périon and Hamid Vahdati Nasab from Tarbiat Modares University in Tehran re-studied the "Qaleh Rad" cave in northern Iran, located at the western edge of the central Iranian plateau, overseen by the Zagros mountains. The cave, at an altitude of 2,137 meters, had been excavated decades ago, uncovering carved stone tools near the cave's entrance. The new excavations, reaching a depth of two and a half meters over an area of just 11 square meters, yielded "tens of thousands of artifacts," as stated by Gilles Périon.

Among these artifacts were numerous horse and wild donkey bones showing signs of butchery, and cut stone tools used in food preparation. These discoveries provide a rich source of data that can be temporally located, as they remain in place across several layers, the deepest dating back 452,000 years and the most recent to 165,000 years. The findings culminated in the discovery of a human milk tooth, which cannot be directly dated but is located in a layer estimated to be between 165,000 and 175,000 years old, making it the oldest known tooth ever found in an area that had previously not shown any clearly dated human evidence older than 80,000 years, according to the Museum of Man.

The milk tooth exhibited signs of abscess, decay, and nearly complete root resorption, indicating it likely fell naturally in the area where this group was living. The researcher noted, "We can imagine human groups using the cave to live in, eat in... without continuously occupying it." At over 2,000 meters above sea level, during this geological period of the middle Ice Age characterized by glacial periods, accessing the site was certainly not available year-round. Due to the scarcity of human remains at the site, it is not possible to determine which species or species inhabited it.

Gilles Périon explained that excavations continue at the Qaleh Rad site, hoping to include "other sites from these periods in this vast area to form a better understanding of the complexity of human settlement."