A few days ago, Shiite religious authority Ali al-Sistani joined the fight against drug abuse, issuing a fatwa stating that "addiction nullifies the right of custody," while reiterating that "drugs are prohibited in all forms," and that "the money obtained through them is forbidden and one should not deal with it." The Parliamentary Anti-Drug Committee viewed al-Sistani's fatwas as a "roadmap for combating the drug epidemic," highlighting the significant influence of the Shiite religious authority on many Iraqis, according to a report published by the "Raise Your Voice" website.

"To Najaf go the hearts of those seeking the seat of power since the establishment of the modern Iraqi state in 1920, up to the last government," says Ali Yusuf al-Shukri in his study published by the University of Kufa titled "Shiites of Iraq: From Opposition to Authority," illustrating the role of the religious authority in Najaf in influencing political decision-making in Iraq, especially through fatwas. These fatwas serve as a model for previous instances where the religious authority played a crucial role in sensitive or problematic issues.

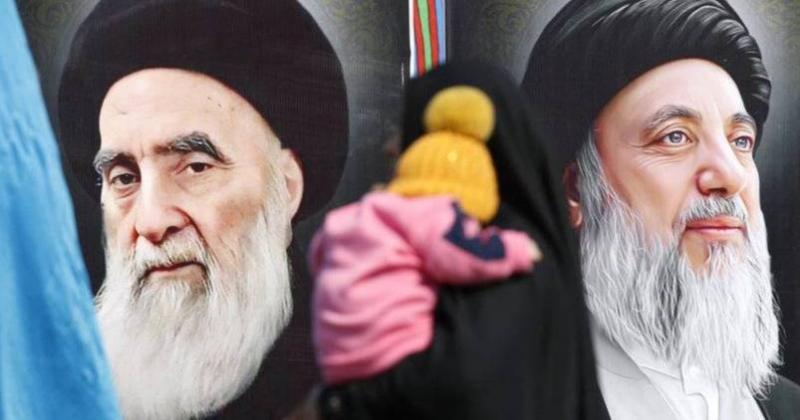

In practical terms, it is possible to observe the continuous interventions of the Shiite religious institution in Iraq's political organization, according to historian Adel Bukwan in his book "Iraq: A Century of Bankruptcy." Bukwan reviews the role of the religious authority and its influence on the Shiite community, not just in Iraq but among over 200 million Shiites worldwide. He sees Najaf as equivalent to the Vatican for Shiites. Until recently, it was composed of four grand scholars: Muhammad Ishaq al-Fayyad, Bashir al-Najafi, Muhammad Saeed al-Hakim (who died in 2021), and Ali al-Sistani.

Bukwan recalls the competition that arose between al-Sistani and Ayatollah Muhammad Muhammad Sadiq al-Sadr for religious authority after the death of Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei. However, the assassination of al-Sadr by Saddam Hussein in 1999 opened the door wide for al-Sistani, who became regarded as the primary religious authority from that moment onward.

The group of scholars present in Najaf, led by al-Sistani, shapes the religious authority and does not officially commit to the "Wilayat al-Faqih" theory adopted by Iran after the fall of the Shah. Instead, "the Najaf authority adheres to a clear principle of separation between politics and religion," according to Bukwan. Nonetheless, this has not prevented the authority from intervening in political affairs when it sees an urgent necessity.

The religious authority played a fundamental role in Iraq after 2003, particularly during the drafting of the constitution, and was decisive in encouraging Iraqis to resort to the ballot boxes in the first parliamentary elections after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime. At that time, al-Sistani issued fatwas calling for participation in voting as a sacred duty, as mentioned by Uday Dawshi in his book "Iraq: Political History from Independence to Occupation."

Bukwan quotes Paul Bremer, the civilian administrator and head of the temporary Coalition Provisional Authority at the time, who stated that al-Sistani encouraged his followers to engage in the political process after 2003. This resulted in turnout rates in Shiite areas during the 2005 elections reaching 70 percent.

Moreover, the religious authority played a central role in declaring war against ISIS in 2014 through the fatwa of "Jihad al-Kafai," which later allowed for the establishment of the Popular Mobilization Forces. Bukwan also mentions the authority’s role in appointing Adil Abdul-Mahdi as prime minister and subsequently in urging him to resign after the October protests of 2019.

Al-Sistani held the Iraqi government accountable for "the killing of dozens of protesters in the country," calling on the authorities to identify the "undisciplined" security forces. Later, he took a firmer stance calling on the Parliament to withdraw confidence from Abdul-Mahdi's government, which precipitated his resignation.

According to Bukwan, these matters "are just a few examples of the interventions of the religious authority in Iraq's political administration." He interprets this by suggesting that "Iraqi political figures often seek the authority's intervention because they are trapped in a fierce conflict that leads to significant fragmentation during crises," thus they turn to the authority as a pillar of stability to decide what they cannot settle themselves.

#### Historical Milestones Before 2003

The role of the religious authority in sensitive junctures in Iraq’s modern history is not new and is not limited to the period after 2003; indeed, the authority has played various roles since the establishment of the Iraqi state. When the highest Shiite authority Kadhim al-Yazdi died on April 30, 1919, Mirza Muhammad Taqi al-Shirazi succeeded him as the religious authority for the Shiite community, with his first fatwa at that time prohibiting the rule of non-Muslims over Muslims, targeting the British and preventing them from ruling the country, as stated in al-Shukri's study "Shiites of Iraq: From Opposition to Authority."

Following this, al-Shirazi issued another fatwa permitting confrontation with the governor-general in Baghdad and demanding a national government and an Islamic ruler. This fatwa is considered, according to al-Shukri, "a practical step and a real precursor to the revolution against the occupation." Later, al-Shirazi issued what he termed "the fatwa of defense," stating that "demanding rights is an obligation for Iraqis, and they must, in the meantime, maintain peace and security, and they may resort to defensive force if the British refuse to respond to their demands."

Al-Shukri sees that the "Revolution of 1920" revealed to the British "the danger that the religious authority poses to British interests in Iraq... this means the British were not reassured about their interests as long as the religious authority plays a significant role in political life."

In 1964, Abdul Salam Arif was in power when Iraqi forces launched a massive attack on Kurdish areas. In an attempt to win over the highest Shiite authority, one of Arif's nationalist associates visited the grand scholar asking him to issue a fatwa permitting the fighting of the Kurds, but the authority expelled him from his home, according to al-Shukri.

In response, the government forged a statement in the name of the religious authority permitting the fighting of the Kurds, to which the authority, led by Mohsen al-Hakim, quickly issued a statement denying the news, condemning the forgery of a statement in its name, and called for a conference in Karbala, which condemned the government and confirmed the prohibition of fighting the Kurds. The authority did not stop there but issued a clear fatwa prohibiting the fighting of the Kurdish people. This led to many Shiites failing to join military units, causing a rupture in the military establishment.

Historian Kamal Dib in his book "A Brief History of Iraq" believes the religious authority played a significant role in directing many Shiite youths toward the Islamic Dawa Party after its establishment in 1957, especially after the Shiite religious authorities issued fatwas against membership in the communist party in 1960. The authority of Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr is considered the spiritual father of the Dawa Party before he withdrew from political engagement. His image continues to adorn the headquarters of various formations that emerged from the party.

Shortly after the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War, Saddam Hussein sent some of his leaders to the highest authority, Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei, to issue a fatwa against the Iranian rulers, but the authority refused to issue such a fatwa. Saddam, as mentioned by al-Shukri in his study, through various intermediaries sought the highest authority in Najaf for a fatwa that would tilt the scales in his favor during the war, but al-Khoei refused, even going so far as to prohibit membership in the Ba'ath Party. The regime's response was swift, with the assassination of al-Khoei's son-in-law, Nasrallah al-Mustafid, a few months later.

Following Iraq's invasion of Kuwait and the rampant looting and plundering of public and private property in Kuwait, al-Khoei issued a fatwa prohibiting the buying and selling of Kuwaiti goods and the prohibition of praying in Kuwaiti homes as they were "usurped properties."