A cosmic coincidence has allowed scientists to look billions of years back in time and observe a star that formed approximately 12.9 billion years ago. This star was spotted by the famous Hubble Telescope through unusual ripples caused by the distortion of the fabric of "spacetime," leading to its designation as "Earendel," meaning "morning star" in Old English, as it shone early in the first billion years following the Big Bang, when the universe was still just an infant, representing barely 7% of its current age of 13.8 billion years.

The mass of this most distant star discovered so far is 50 times that of the Sun, yet it is millions of times brighter, according to astronomer Brian Welch from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, who is the lead author of a research paper published yesterday in the prestigious British scientific journal Nature. Information has also been gathered from various Western media, including the British newspaper The Times.

Previously, Icarus, known as a blue giant in the constellation of Leo, was the farthest star observed by humans through telescopes, located 9 billion light-years from Earth and formed when the universe was approximately 4 billion years old, or about 30% of its current age. However, the newly discovered "Earendel" was reported by NASA as "one for the record books," with a distance of 28 billion light-years.

Dr. Welch expressed his astonishment about the star, saying, "We could hardly believe it (the distance), it made it seem as if we were reading an interesting book, but we started with chapter two, and now we have the chance to see how everything began," referencing the origin of the universe and the emergence of existence through the Big Bang.

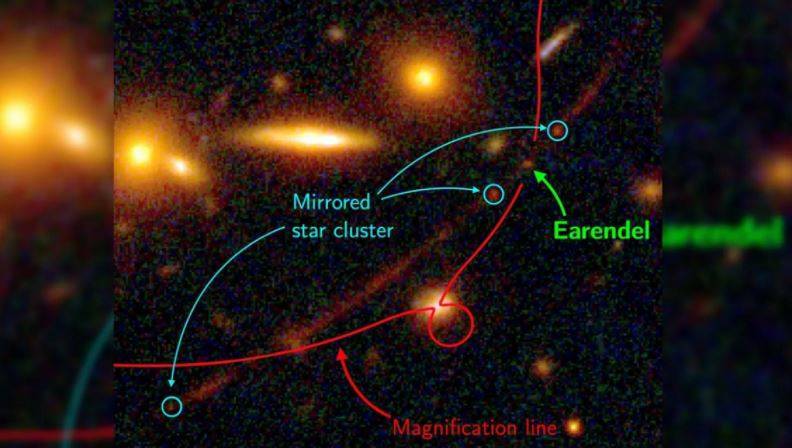

Despite its extraordinary mass and brilliance, the discovery of Earendel would not have been possible without a chance occurrence that placed it near a huge cluster of galaxies known as WHL0137-08. This cluster is so massive that its gravity distorts the fabric of space, creating a natural gravitational lens that amplifies the light from the objects behind it. This phenomenon, known as "gravitational lensing," resulted in the star appearing a thousand times brighter, "much like ripples on the surface of a swimming pool, acting as magnifying lenses to create patterns of bright light at the bottom of the pool on a sunny day," as explained by astronomer Welch.

Welch also noted, "Typically, galaxies at such distant distances appear as small blobs, where the light from millions of stars mixes together, acting as a lens that amplifies the star located behind it." This will provide insights for the James Webb Telescope, set to be operational next June, based on findings from the study co-authored by another astronomer, Dr. Dan Coe from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, which conducts scientific operations for Hubble, while the Goddard Space Flight Center of NASA in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope.

Moreover, the James Webb Telescope, in its orbit at 1.6 million kilometers from Earth and equipped with new technologies, will be able to perform observations of Earendel that Hubble, which is set to retire this year after 32 years of service, cannot achieve, including measurements of the star's brightness, temperature, and composition.