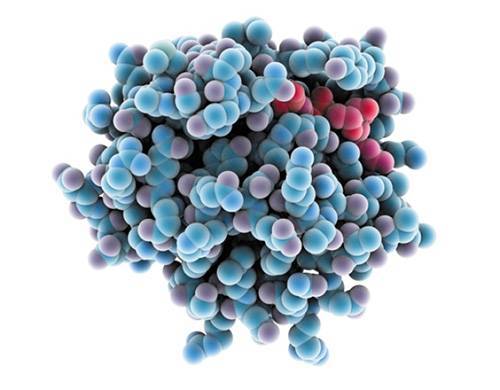

Some cancer researchers at Vanderbilt University have discovered a protein that can be genetically manipulated to prevent it from interacting with the gene responsible for tumor development, effectively dissolving tumors within days. Professor William Tansy, a professor of cell biology, evolutionary biology, and biochemistry at the university, states that his work is dedicated to understanding how the MYC oncogene works. This noodle-like protein plays significant roles in normal human development and is often reactivated in the most deadly and difficult-to-treat cancers.

Regarding cancer recurrence, Tansy said: "When cancer strikes, MYC genes become like the nitro material used in cars; they lead to relentless cycles of cell duplication and division. The faster cells grow and divide, the more mutations accumulate, leading to cancer cell growth." He explained that the MYC gene has been an elusive therapeutic target for at least 30 years and was considered indestructible due to a lack of amendable genetic structure. To overcome this barrier, Tansy began identifying the most organized partner proteins of the MYC gene with the aim of engineering mutations that disrupt interactions between these partners and the MYC gene, which causes cancer cell growth. He stated, "If we can validate the physical connection between MYC and partner proteins, we can genetically engineer and certainly treat it."

During the study, Tansy and his colleagues identified Host Cell Factor-1 (HCF1) as a specific candidate for this kind of therapeutic development since HCF1 was linked to the MYC gene, which is significant for protein synthesis. When a cancer cell associated with the MYC gene is genetically designed not to interact with HCF1, the cancer cell begins to self-destruct, making the development of this treatment, which relies on reducing this interaction, a very promising step in cancer therapy.

Tansy also stated, "What is interesting is that we do not need to eliminate all functions of the MYC gene; it is similar to the Achilles' heel dilemma. We only need to target a very specific interaction and prevent it from occurring." It is noteworthy that this is the second protein discovered by Tansy that responds to the cancer-causing MYC genes. A previous find of the WDR5 protein in collaboration with Stephen Vessick, a professor at the Orrin H. Ingram II Cancer Research Center, exhibited similar behavior to this protein. What is truly surprising is that both proteins were hiding in plain sight all along. Tansy explains: "The MYC gene actually binds to DNA to activate other genes; transcription factors only need two domains: a DNA binding domain and an activation domain that stimulates DNA to produce RNA and the necessary proteins for cell reproduction. Therefore, we are interested in the remaining piece, the solitary piece of protein that had not been seriously considered before."

As a result of four years of hard work, Tansy’s lab intends to gain a greater understanding of how HCF1 works and its connection to MYC, how it affects the functions of other genes, and ways to use it in cancer treatment.