Sudanese authorities have taken control of several profitable entities that have provided support to Hamas for years, highlighting how far Sudan has come in its role as a haven for the Palestinian movement under the former president Omar al-Bashir's rule. The seizure of at least 12 companies believed to be linked to Hamas has expedited Sudan's alignment with the West since the ousting of Bashir in 2019. Over the past year, Sudan successfully removed itself from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism and is edging closer to debt relief exceeding $50 billion.

Sudanese and Palestinian analysts have indicated that Hamas has lost an external base where its members and supporters could live, raise funds, and smuggle Iranian weapons and money into Gaza. Details provided by Sudanese official sources on the seized wealth, along with information from a Western intelligence source, illustrate the extent of these networks. Officials from a task force formed to dismantle Bashir's regime state that the seized assets include properties, shares in companies, a hotel in a prime location in Khartoum, a currency exchange company, a television station, and over a million acres of agricultural land.

Wajdi Saleh, a prominent member of the task force called the Committee for Dismantling the 30 June 1989 Regime and Recovering Public Funds, remarked that Sudan had turned into a hub for money laundering and terrorism financing. He added that the regime had become “a large cover and a massive umbrella both internally and externally.” A source in a Western intelligence agency indicated that the methods used in Sudan are common in organized crime circles. There were authorized shareholders who ran companies, with rents collected in cash and transfers made through currency exchange offices.

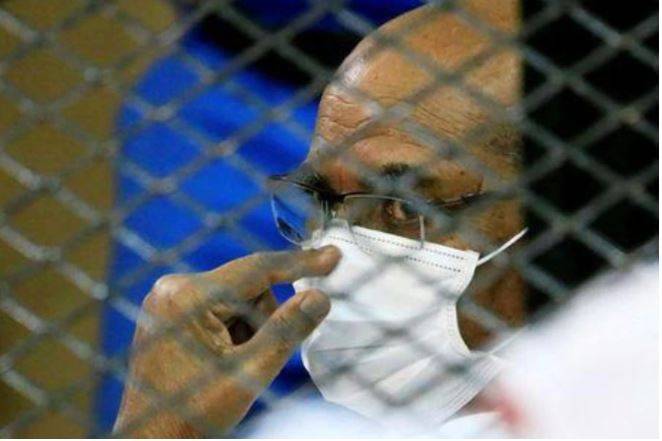

Bashir openly supported Hamas and had friendly relations with its leaders. A committee member, speaking on condition of anonymity, noted that they received preferential treatment in tenders, tax exemptions, and were allowed to transfer money to Hamas and Gaza without restrictions.

### A Center for Islamists

Sudan's transformation from a pariah state to a U.S. ally was gradual. In the ten years following Bashir’s seizure of power in 1989, Sudan became a hub for Islamic extremists and provided shelter to Osama bin Laden for several years, resulting in U.S. sanctions due to its connections with Palestinian militants. Subsequently, Bashir attempted to distance himself from Islamic extremism by enhancing security cooperation with Washington. In 2016, Sudan severed ties with Iran, and the following year, U.S. trade sanctions on Khartoum were lifted after Washington accepted a halt to state support for Hamas.

However, networks that supported Hamas remained intact until Bashir's fall. An official from the 30 June Dismantling Committee stated that Hamas's investments in Sudan began with small ventures like fast-food restaurants before expanding into real estate and construction. One example is the Hassaan and Al-Abid company, which initially started as a cement company and grew into major real estate development ventures. The committee claims these companies were part of a network of about ten other major companies whose ownership stakes were intertwined and linked to Abdel Basit Hamza, a Bashir ally, which transferred large sums through foreign bank accounts.

The largest of these companies was Al-Ruwad for Real Estate Development, established in 2007 and listed on the Khartoum Stock Exchange. It had subsidiaries that a Western intelligence source claimed were involved in money laundering and currency dealings to finance Hamas. Hamza was sentenced to ten years in prison for corruption in April and was transferred to the same prison as Bashir in Khartoum. The committee stated that his wealth amounts to $1.2 billion. Hamza’s lawyer, who also represents Bashir, could not be reached for comment.

A second network valued at $20 million revolved around the Tayba television channel and a related charity called Al-Mishka. Maher Abu Al-Jukh, an administrator hired to manage Tayba, noted that the channel was operated by two Hamas members who obtained citizenship and owned business interests and properties. He added that the television channel was involved in smuggling money from the Gulf and laundering millions of dollars.

In a statement to Reuters, Sami Abu Zuhri, a Hamas official, denied that the movement had investments in Sudan but acknowledged the political transformation in Sudan, stating, “Unfortunately, many measures have weakened the movement's presence in the country and limited its relations.”

### Normalization

By last year, Sudan was fervently working to be removed from the list of state sponsors of terrorism, a prerequisite for debt relief and support from international lending sources. Under pressure from the United States, Sudan joined the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Morocco in agreeing to normalize relations with Israel, despite slow progress in implementing this agreement. A former American diplomat specializing in Sudan during the Trump administration stated that closing the Hamas network was central to negotiations with Khartoum.

The U.S. provided Sudan with a list of companies that needed to be shut down, according to a Sudanese source and a Western intelligence source. The U.S. State Department declined to comment. The official from the 30 June Dismantling Committee mentioned that several figures connected to Hamas had moved to Turkey with some liquid assets but left behind about 80 percent of their investments.

Sudanese analyst Magdy Al-Ghazouli stated that the transitional leadership in Sudan “consider themselves the direct counter to Bashir regionally.” He added that they “want to market themselves as part of the new security system in the region.” Palestinian analyst Adnan Abu Amer noted, “The coup against Bashir created a real problem for Hamas and Iran,” adding, “Hamas and Iran now have to think about alternatives that did not exist because the coup against Bashir was unexpected.”