The balance of power in the Lebanese Parliament necessitates an agreement among the political blocs represented therein to elect a president to succeed former President Michel Aoun. This is being pushed by broad political blocs. Without this agreement, it seems unlikely that the current presidential vacuum, which has persisted since the beginning of November, can be filled, as the philosophy of "pluralistic governance" in Lebanon is based on ensuring "charter compliance" between Muslims and Christians, according to former Deputy Speaker of Parliament Eli Farachely, who emphasizes that protecting the Taif Agreement should be a priority for the next president.

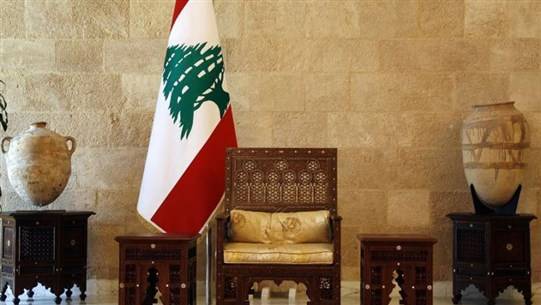

The Lebanese Parliament is evenly divided between Muslims and Christians, and these groups are fragmented among various political options, some of which converge on specific issues while others diverge, including the political identity of the next president and the list of their tasks. In the absence of an agreement among political forces, the parliament has failed six times to end the presidential void, with some asserting that consensus is a necessary pathway for electing a president.

The Lebanese system is based on "consensual democracy," which, according to Lebanese practice, means giving each faction the right of "veto," ensuring governance by key leaders, and ruling by proportional representation. This mandates an agreement among two-thirds of the forces represented in parliament to elect a president, or at least a consensus among half of them to assign a prime minister or pass essential laws. Since the signing of the Taif Agreement in the late 1990s until 2018, there were often majorities capable of resolving issues, largely sidelining internal opposition and paralyzing the democratic system due to a lack of accountability, before the situation changed in 2018 with the adoption of a proportional voting system that produced minorities and majorities, necessitating further agreements.

Former Deputy Speaker Eli Farachely told "Asharq Al-Awsat" that "the defect in the previous electoral laws based on the majority system was corrected in the latest law, which, despite its flaws, significantly improved the Christian representation in the parliament," bringing the opposition into the parliament and resulting in a "real exercise" of the democratic system between a ruling majority and an opposing minority. However, this scenario has hindered the election of a new president, a reality that Farachely attributes to "the actual divide in the parliament under a mandatory passage represented by securing the presence of two-thirds of the parliament members, rendering the assembly incapable of producing a president by a majority or minority."

Farachely asserts that "the philosophy of pluralistic governance is based on ensuring charter compliance between Muslims and Christians, which means that there must be an agreement" among the components. In the absence of such an agreement, "this necessitates a regional agreement that reaffirms the obligation of the president to adhere to and protect the Taif Agreement." The "Taif Agreement" is the national reconciliation document reached by the Lebanese in 1989 under the auspices of Saudi Arabia, which ended the Lebanese civil war and enshrined power-sharing between Muslims and Christians regardless of their numbers. Some propose the idea of modifying or developing the system, while many oppose that, demanding the full application of the Taif Agreement, which has become the second constitution of the Lebanese Republic.

Farachely stresses that "the danger today is on the Taif Agreement, not a struggle over electing a president," warning that the aim behind attempts to create new precedents and to question the constitution and its practice over the past years "is to undermine the Taif Agreement." He calls for an agreement on key principles that would make the next president a "president of tasks."

Farachely clarifies that defending and adopting the Taif Agreement should be "a priority and the central task" for the next president, in addition to other tasks, including "being able to engage in dialogue with Hezbollah regarding its weapons and presenting it for discussion through a defensive strategy," and "being capable of correcting relations with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries, which represent the lifeblood of Lebanon." He adds that the next president "should also have the ability to communicate with Syria to delineate maritime borders and discuss the issue of Syrian refugees to resolve this matter," as well as "be reassuring to Christians and not exacerbate their divisions." He indicated that these specifications "I see in candidate Suleiman Franjieh, or any other figure who meets these tasks."

The vertical division among Lebanese components prevents reaching a consensus on a single political figure and established criteria, and after six parliamentary sessions, no new president has been elected. In this context, General Director of General Security, Major General Abbas Ibrahim, said that "the anxiety felt by the Lebanese amid this storm that still resides in our country and the region necessitates that all officials rise above all disagreements, adopt a constructive dialogue, and work towards rebuilding our state to live in it in peace and stability, as it is the only guarantee after God."