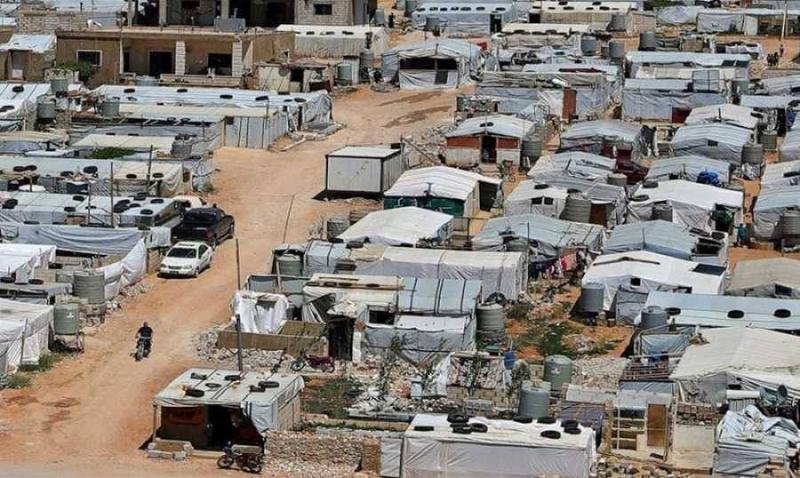

The issue of Syrian displacement in Lebanon competes with the horrors of limited warfare in the south and the protracted presidential vacuum in the country. The refugee crisis, which has escalated into a snowball effect since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011, is now on the brink of explosion due to the multifaceted burden created by the presence of more than two million Syrians in the crisis-stricken nation facing enormous economic, financial, political, security, and societal challenges, as reported by "Al-Rai" in Kuwait.

It is no longer surprising that Syrian displacement is one of the three pressing issues on the table in any Lebanese regional or international discussions, much like the recent talks held by caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati with French President Emmanuel Macron in Paris, prior to his first communication with his Syrian counterpart, Hussein Arnous, to discuss the need for coordination on the deportation of approximately 2,500 convicted criminals and prisoners back to Syria.

As the anticipated visit of Cypriot President Nikos Christodoulides alongside European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen approaches, doubts persist about the potential success of efforts to defuse the timebomb that is the displacement dossier, which risks explosion at any moment. Over nearly 13 years, the displacement crisis has deepened, evolving into a humanitarian, political, economic, demographic, and social problem that intertwines Lebanon, Syria, and European refugee host countries like Cyprus, Greece, and Italy, reaching the United Nations and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, along with the United States and other Western nations involved in the Caesar Act and the Syrian file.

It is widely accepted that this issue is governed by the intersection of two types of fear:

- The first fears international anger should any forced repatriation of refugees occur, leading to a pragmatic effort to exchange their current status quo for additional billions in aid.

- The second seeks to avoid provoking the regime of President Bashar al-Assad, considered an adversary in Lebanon, who is the primary obstacle to their safe return and aims to leverage the refugees and Lebanon as pressure points against the West for concessions in the reconstruction of Syria and for breaking the sanctions belt.

This is a heavy burden that poses escalating implications, nearly suffocating the Lebanese entity—state and people alike. While solutions are not solely in the hands of the Lebanese, they can certainly take preliminary steps to organize the presence of Syrians on their territory while awaiting consensus among local, international, and regional parties to outline a roadmap for the return of refugees and commitment to it.

The fierce campaigns targeting Syrian refugees in Lebanon recently sounded the alarm that the pressure cooker has reached a boiling point, warning of a potential explosive outburst at any moment. Daily incidents of murder, theft, and assaults perpetrated by Syrians, along with an unprecedented overcrowding of Lebanese prisons—where Syrians reportedly account for about 40 percent of the total prison population according to Internal Security Forces sources—have increased crime rates by 100 percent, with Syrians constituting 60 percent of offenders based on General Security statistics.

The recent abduction and murder of political figure Pascal Sleiman by a Syrian gang nearly plunged the country into severe internal unrest. Alarming figures leave Lebanese citizens feeling anxious and cautious, countered by a humanitarian and rights-based perspective claiming that among the 2,300,000 Syrian refugees, the rate of criminals should not exceed 5 percent, while the remaining refugees seek safety and require humanitarian solutions that uphold their fundamental rights, foremost among them being not to be coerced into forced returns to Syria and to avoid the biopolitics being exercised by certain municipalities in Lebanon which regulate their daily lives and monitor their movements in ways that strip them of their humanity.

The issue of Syrian refugees was raised by MP Strida Jaafar with the Minister of Interior and Municipalities, Judge Bassam al-Mawlawi, following Pascal Sleiman’s murder, announcing documented figures of these individuals in some Lebanese districts. She noted that the region of Bsharri has managed to significantly organize and reduce their presence to approximately 1,000 laborers in winter and about 1,800 in summer during the apple-picking season, while numbers in other Christian districts are escalating, reaching 40,000 in Batroun, 62,000 in Zgharta, 30,000 in Koura, and 50,000 in Kesrouan. The Metn region hosts the largest number with 150,000 refugees, bringing the total in Mount Lebanon and the Jiza region to about 830,000.

Jaafar requested the interior minister's assistance for municipalities, through cooperation with security forces, to apply previous decrees concerning the organization of Syrian presence, especially since Lebanon is not a refuge country under international law but a transit country. It must be emphasized here that Lebanon did not sign the 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, which governs the integration of refugees in host countries. Memorandums on this matter were signed in 2003 between Lebanese General Security and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

The Minister of Interior declared in a press conference that only 300,000 of the Syrians present in Lebanon hold legal residency, while 800,000 are registered and around 1.2 million are residing illegally and without registration. Since May 2023, the minister has instructed governors, through them to the mayors and local officials in villages housing refugees, to launch a national campaign for a census and registration of Syrian refugees and to document all residents within its jurisdiction.

He also instructed all local officials not to process any paperwork or issuance for any Syrian refugee without proof of their registration, emphasizing that no property should be rented to any refugee without confirming their registration with the municipality and possession of a legal residency in Lebanon. Additionally, a field survey of all institutions and self-employed refugees should be conducted to verify their legal licenses.

A letter was sent to the Ministry of Justice, hoping to disseminate instructions to all notaries not to validate any document or contract for any Syrian refugee without a proof of their registration at the municipality. However, as acknowledged by many municipalities, nearly a year after these letters were issued, it is challenging if not impossible to enforce them, given the intertwining interests between Lebanese and Syrians on one hand, and the lack of human and logistical resources within municipalities to implement these decisions.

Even the threatening notices issued by some local forces to intimidate Syrians, demanding that anyone lacking legal residency leave town and not return, are seen as mere intimidation tactics impossible to enforce on the ground.

During a conference held in March 2024 at the General Directorate of General Security, organized by the Ministry of Interior to launch a roadmap for organizing the legal status of Syrian refugees and their return, Acting General Director Elias Beisari stated: "We have recently received a database from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, comprising 1,486,000 refugees, without classification or indication of the registration date or entry into Lebanon, complicating the determination of their legal status." Recent statistics show that registered refugee numbers have dropped from 2015 to today to approximately 785,000 refugees, indicating a discrepancy in numbers and an inability to determine an accurate count of refugees in light of the inability to conduct a comprehensive survey of them.

Betty Hindi, head of the "Bayt Lubnan" organization, stated at the conference that Lebanon is the first country in the world in terms of the number of refugees relative to its population. This situation threatens security and identity, as for every two Lebanese people in Lebanon, there is one Syrian refugee, and for every birth of a Lebanese child, there are four births of Syrian children without documentation. The Lebanese population increases by 1 percent annually, while the Syrian population rises by 4 percent annually.

According to these rates, the number of Syrian refugees will equal the number of Lebanese citizens in the foreseeable future. The direct cost of displacement on Lebanon is around $1.5 billion annually, according to the World Bank, while the indirect cost is $3 billion, totaling $4.5 billion yearly, which over 13 years amounts to approximately $58 billion. Some question these figures, viewing them as exaggerated, and refuse to attribute the economic crisis to the Syrian presence in Lebanon. The most prominent skeptics are organizations operating in the field of human rights and refugee assistance.

The role of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in Lebanon is not hidden, as it has contributed, through monthly aid provided in US dollars to registered refugees, to encouraging these individuals to remain in Lebanon instead of returning to Syria and increasing the number of illegal entrants into Lebanon seeking to register with the commissioner and receive aid, despite the fact that registration has officially ceased since 2015, according to the commissioner. However, this declaration is contradicted by the mayor of Al-Qaa, Bashir Matar, who states to "Al-Rai," that the current influx of refugees is not due to war but is economic displacement, with 90 percent of young men entering Lebanese territory being wanted for compulsory military service.

He asserts that it is not true that the UN Refugee Agency ceased registration since 2015, but continued it in a non-official manner. Everyone who enters illegally submits their papers to the commission for registration, which is evident in our region. Many refugees have obtained counterfeit residency cards, which they have used to open businesses.

The UN Refugee Agency, which we attempted to communicate with for comments from its officials, advised us not to delve further into this subject due to the current volatile situation on the ground. It is striving to manage affairs and prevent an explosion between Lebanese and Syrians, despite being fully aware of the rising number of crimes perpetrated by Syrian refugees.

The advertising campaign "UNDO The Damage," directed specifically at the High Commissioner, has sparked a wave of outrage, as it made the agency the main reason for attempts at integrating Syrians into Lebanese society and preventing their return to Syria, thereby risking a demographic and population explosion. Close associates of the agency, both inside and outside Lebanon, attempted to dissuade Sami Saab, the campaign's creator and implementer, from proceeding, and efforts were made to launch counter-campaigns and accuse him of racism against Syrians to mitigate the impacts of the campaign, which most Lebanese responded to positively. Saab confirms that pressure on the agency is the only way to resolve the refugee issue and that it must address the growing harm to Lebanon. For instance, the agency resettled only 7,490 Syrian refugees residing in Lebanon in 2022.

During a seminar on Syrian displacement and refugee returns, Dr. Ali Faour, a demographic studies expert, presented maps and documents confirming that the reasons behind the delayed return of refugees are related to international community opposition to a return plan before a political solution, tightening the blockade on Syria, and the subsequent decline of financial support from international donors. Faour focused on the role of the UN Refugee Agency, along with other international organizations, in executing comprehensive integration operations within Lebanese territories and their failure to abide by Lebanese laws, which now threaten Lebanon's demographics and identity after 13 years of hosting refugees.

The study he conducted indicated that one of the main obstacles preventing the return of refugees is the cash assistance that also encourages further waves of migration, especially among youth coming to Lebanon for the financial, health, educational, and nutritional support provided by the UN in the country of cedars, resulting in the number of refugees multiplying in many areas, particularly in the Beqaa plains bordering the land border with Syria, as well as in northern areas like Tripoli, Akkar, and al-Dunniyeh, Batroun, and the impoverished suburbs of Beirut and Sidon.

The study concludes that the return of Syrian refugees is highly unlikely; Lebanon has become a large camp for long-term Syrian displacement unparalleled in the world. The bitter cup has reached Cyprus and Greece, where the numbers of refugees heading to these countries illegally from Lebanon are increasing, and the small island is no longer capable of accommodating the rising numbers. This compelled its president, Nikos Christodoulides, to visit Lebanon leading a ministerial delegation to discuss this issue and urge stricter measures to prevent illegal migration. Lebanon's response was to seek cooperation from Cyprus to pressure European countries to find solutions for the displacement issue; otherwise, its explosion threatens all the countries in the region.

While awaiting the end of May, when an international conference will be held in Brussels to discuss the displacement crisis, local solutions are proposed in Lebanon, the foremost of which is conducting a comprehensive survey of the number of refugees in Lebanon in collaboration with municipalities to maintain the status of all refugees who meet the agency’s conditions, while closing the files of those who do not meet these criteria and halting their aid. As for their departure, it will either be voluntarily and of their own accord adhering to Lebanese laws or through return convoys organized by official Lebanese authorities in cooperation with Syrian entities, or by deporting those unwilling to return to a third country considered a refuge rather than merely a transit country like Lebanon.

However, can the donor countries, especially European ones, agree to this proposed solution, which exposes them to new waves of migration?