After the COVID-19 pandemic, doctors began diagnosing unusual and rare cancers in individuals of various ages, reinvigorating a well-known idea among health experts that viruses can cause cancer to appear or bring it back to the forefront quickly. A report from The Washington Post quotes Dr. Kashyap Patel, who, in 2021—one year after the COVID-19 pandemic—diagnosed a patient in his forties with cholangiocarcinoma, a rare and deadly cancer of the bile ducts that typically affects individuals in their 70s and 80s. When Patel informed his colleagues, they too began to reveal that they had recently treated patients with similar diagnoses. Within a year of that meeting, the hospital recorded seven such cases.

Patel, the CEO of Carolina Blood and Cancer Care Associates, stated, "I have practiced medicine for 23 years and have never seen anything like this before." Another oncologist, Asutosh Gaur, agreed, saying, "It shook us all." There was another oddity: Many of the patients were dealing with multiple types of cancer arising almost simultaneously, alongside more than a dozen new cases of other rare cancers. The rise in aggressive late-stage cancers since the pandemic has been confirmed by some early national data and several major cancer institutions, according to the report.

The idea that certain viruses can cause or accelerate cancer is not new. Scientists have recognized this possibility since the 1960s, and today researchers estimate that 15 to 20 percent of all cancers worldwide arise from infectious factors such as the human papillomavirus and hepatitis B. It may take many years before the world gets definitive answers on whether COVID-19 is behind the increase in cancer cases, but Patel and others concerned are calling on the U.S. government to prioritize this question, knowing it could impact the treatment and management of millions of cancer patients for decades to come.

There is no real data linking COVID-19 to cancer, and some scientists remain skeptical. John T. Schiller, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health and a leader in studying cancer-causing viruses, stated that pathogens known to cause cancer tend to persist in the body long-term. However, the class of respiratory viruses that includes influenza and COVID-19 typically infects the patient and then disappears rather than remaining and is not thought to cause cancer.

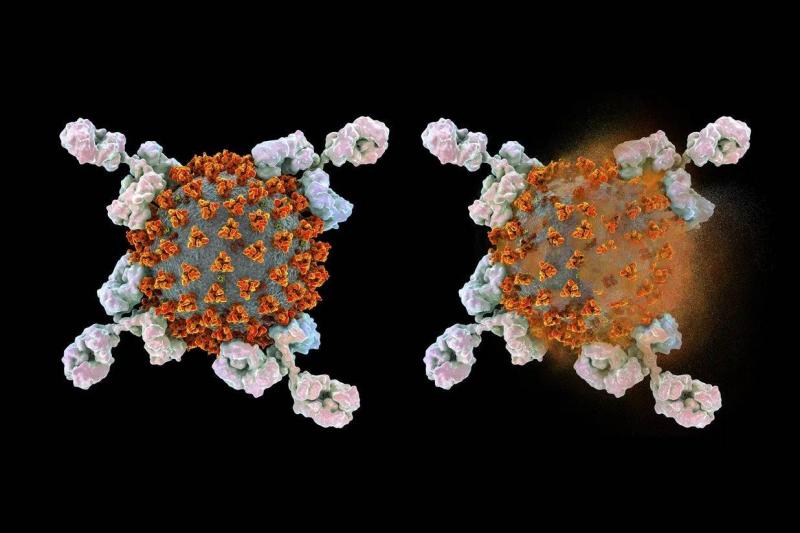

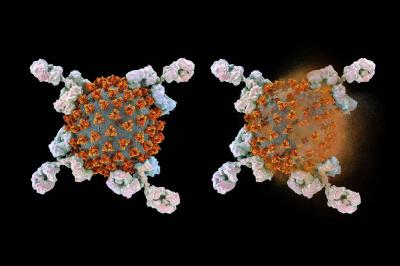

David Tuveson, director of the Cancer Center at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and past president of the American Association for Cancer Research, indicated there is no evidence that COVID-19 directly transforms cells to make them cancerous. However, this may not be the complete story. Tuveson explained that several small, early studies—many published in the last nine months—suggest that COVID-19 infection can trigger an inflammatory cascade and other responses that could theoretically exacerbate the growth of cancer cells. He added, "COVID wreaks havoc on the body, and that’s where cancers can start."

Even in the early wave of COVID-19 in the U.S., public health officials anticipated an increase in cancer cases. A paper from The Lancet Oncology analyzed a national registry showing increases in diagnoses of stage 4 cancers, the most severe, by late 2020. Data from the Baptist Health Cancer Institute in Miami, the University of California in San Diego, and other major institutions show consistent increases in late-stage cancers. Shiyusong Han, the scientific director of health services research at the American Cancer Society and the lead author of the "Lancet" study, attributed this surge to some people delaying care due to virus-related fears or economic reasons.

A team at the University of Colorado is investigating whether COVID-19 awakens dormant cancer cells in mice. The preliminary results, reported in a preprint released in April, indicated that when cancer-surviving mice were infected with COVID-19, their dormant cancer cells proliferated in the lungs, and similar findings were obtained with the influenza virus. Ashani Weeraratna, a professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, noted that the Colorado study, in which she did not participate, is part of a new field that has emerged in the past decade, exploring triggers that can awaken cancer cells.