"Basmati rice," a distinctive long-grain rice, has become a battleground at the heart of the conflict between Pakistan and India. According to AFP, India has applied for an exclusive trademark that would grant it sole ownership of basmati rice in the European Union, a move that could significantly damage Pakistan's standing in a vital export market. Ghulam Murtaza, a partner at the Barkat Rice Mills in southern Lahore, Pakistan's second-largest city, said, "It feels like a nuclear bomb has been dropped on us.”

Pakistan immediately opposed India’s recent move, considering it the largest rice exporter in the world, with annual earnings of $6.8 billion, while Pakistan ranks fourth with $2.2 billion, according to UN statistics. The two countries are the only global sources of basmati rice. Murtaza, whose fields are barely five kilometers (three miles) from the Indian border, remarked, "India has caused all this fuss so they can somehow capture one of our target markets," adding that "their rice industry has been affected."

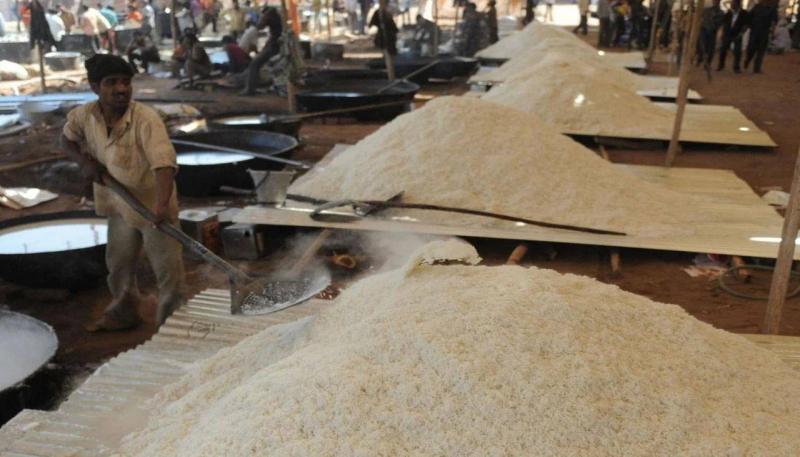

From Karachi to Kolkata, basmati rice is a staple in the daily diets across South Asia, accompanying meat and vegetable curries, and featuring prominently in numerous varieties of biryani served at weddings and celebrations in both countries. Notably, Pakistan has expanded its basmati exports to the EU over the past three years, benefiting from India’s difficulties in meeting the EU’s stricter pesticide standards. Pakistan now fulfills two-thirds of the region's annual demand of approximately 300,000 tons, according to the European Commission.

Faisal Jahangeer, Vice-President of the Pakistan Rice Exporters Association, stated, "For us, this is a very important market," claiming that Pakistani basmati rice is more organic and "better in quality."

To elaborate on India’s application, PGI status grants intellectual property rights to products linked to a geographical area where at least one stage of production, processing, or preparation occurs. For instance, Indian Darjeeling tea, Colombian coffee, and various French meats are among the well-known products enjoying PGI status. This differs from protected designation of origin, which requires all three stages to occur in the relevant region, as seen in cheeses like French Brie or Italian Gorgonzola. These products are legally protected against imitation and misuse in countries that adhere to the protective agreement, allowing them to be sold at higher prices.

India claims it has not asserted in its application that it is the sole producer of the distinguished rice grown at the foothills of the Himalayas, but obtaining PGI status would nonetheless grant it that recognition. Vijay Setia, former president of the Indian Rice Exporters Association, told AFP, "India and Pakistan have been exporting and competing healthily in various markets for nearly 40 years... I don’t think PGI will change that."

A European Commission spokesperson told AFP that according to EU rules, both countries must attempt to negotiate an amicable solution by September, following India’s request for a three-month extension. Legal scholar Delphine Marie Vivian noted, "Historically, the reputation and geographical area (for basmati) are commonalities in India and Pakistan."

After years of delay, the Pakistani government determined the limits of where basmati can be harvested in the country in January. It also announced plans to bestow similar protective status on pink Himalayan salt and other premium agricultural products. Jahangeer expressed hope that Pakistan could persuade India to submit a "joint application" instead, under the banner of the shared heritage represented by basmati rice. He added, "I am confident we will reach a (positive) outcome soon... the world knows that basmati comes from both countries."

If no agreement is reached and the EU ruling favors India, Pakistan could appeal to European courts, but the prolonged review process might leave the rice industry neglected.