Important advancements in human organ transplantation that could save more patients may soon be realized. Scientists from the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Medicine at the University of Minnesota have made a significant breakthrough in biomedicine and organ cryopreservation. They successfully froze mouse kidneys, thawed them, and then re-implanted them back into the mice, where they functioned properly after being warmed.

This technology holds promise for the future of organ transplantation, and if it can be adapted to larger human organs, many patients on the organ transplant waiting list could be saved. Rapid freezing at conditions of 150 degrees Celsius below zero is essential. Such immediate cold prevents ice crystals from forming in the tissues, allowing them to remain intact. A gradual and uniform warming of the entire kidney is then required to prevent degradation.

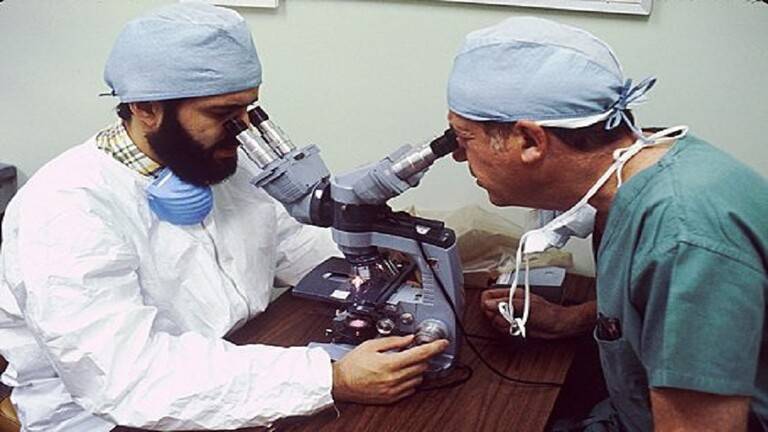

In the university laboratory, nanoscale iron particles introduced into the kidney before freezing facilitated gradual warming through the influence of a magnetic field. Theoretically, similar technology could be used to stimulate nerve cells with heat-sensitive receptors, marking a step toward "reviving" frozen living organisms.

One of the complexities of organ donation lies in the method and timing of delivery. The kidney stored in ice has a limited viability. If we can extend this period without losing organ function, it would be a significant victory. Theoretically, an organ that undergoes rapid cryopreservation and is prepared for later thawing could remain viable for many years.