The first stone in the production chain is the craftsman. In Lebanon, this craftsman is only mentioned during the tourist season, usually in the form of a cedar, purchased by visitors in the old Zouk market or at one of the exhibitions in Jounieh, perhaps in one of the shops in Byblos. It is known that the highest percentage of craftsmen is found in Mount Lebanon at 22.61%, according to a study adopted by the “Nous” Association, which focused on highlighting the economic value of the artisanal sector in Lebanon. In this study, under the classification of self-employed artisans in Mount Lebanon, textiles occupy 7.61%, followed by creative works at 5.77%, wood at 4.99%, handicrafts at 2.62%, and gold at 2.10%.

What is the situation of artisans in Mount Lebanon, and how do they interact with the economic crisis? This is a question posed by "Nidaa al-Watan" to some workers in Kesrouan and Metn. Unfortunately, some crafts are on the verge of extinction. One of these is the production of the “labada” (traditional headgear). What is a labada? Craftsman Youssef Akeek (Hrajel) will directly point you to Mar Charbel, as the labada is a traditional garment worn on the head, which Mar Charbel used to wear. Akeek admits that his nephew's children have not yet fully acquired the craft, making him the last one who knows how to pass down Mar Charbel's legacy, as some refer to it. As for who buys it? Some at exhibitions respond that participation in them is required.

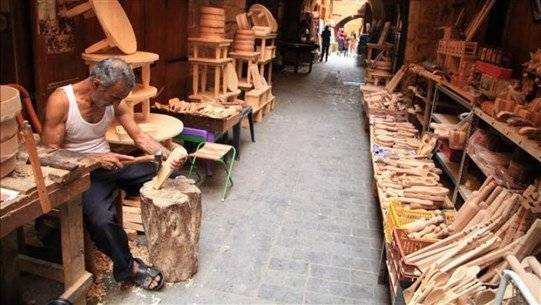

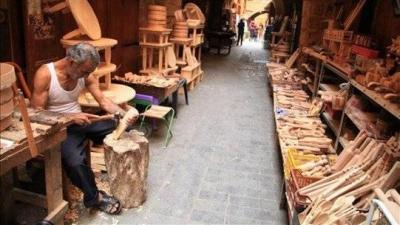

You decide to look for another craft, hoping the situation might be better, and in Zouk Mikael, near Mar Yohanna, you search for a man named Youssef Asakir, about whom you have been informed. He seems like a mayor, given how much he knows about the families' history in the area, but he is not! He has a carpentry workshop and has been producing furniture for 50 years. He has decided to rise against the reality of his situation, describing his day under the current circumstances as simply moving from near his home to the tree where his workshop is located, with nothing else to add. Only a few repairs, which clients are embarrassed to not pay for. What alleviates this burden is that he is not alone in this crisis; otherwise, he would have gone to the nearest neurologist, relying on the saying: "death with the crowd is sweet."

What is causing the decline in work? His voice rises, pointing out that citizens cannot afford a loaf of bread; so how can they afford a sofa that costs around five thousand dollars? As a result, he shifted from furniture making, despite the existence of his workshop, to repair work. You contact Bedros (Borj Hammoud), who has a lathe hoping conditions might be better, but he only responds with a shout as if we are responsible for his condition: "Where's the electricity! I only work an hour a day because there's no electricity." According to him, there is work; however, this craft requires electricity, and it’s impossible to drive a nail without it. He cannot bear the costs of generator electricity.

Some artisans practice more than one craft, like Peter Khatcharian (Antelias), whose original craft is making wooden pipes. His father worked in carpentry, but Peter, due to his love for smoking, wanted to create a pipe from wood. Over thirty years ago, without the internet, he searched in books and succeeded in designing a pipe, leading him to pursue pipe-making which lasts longer than humans. In recent years, work has increased, but he doesn’t link this to rising tobacco prices; he’s just happy about it. Pricing varies based on his experience and the type of wood he describes, which includes details that affect quality, starting at $75 for wood. However, Peter not only persists in pipe-making; he also works as a jeweler for very precious pieces. As long as he has a workspace he inherited from his father, he continues to create, possessing artistic sensibility and the patience to learn.

Meanwhile, the real plight lies with the elderly who know only one skill, like Mari Ayoub, who works in lace, embroidery, crochet, and abayas, starting her shift from 6 PM to 1 AM. She is well-known in the old Zouk market. She chose this path in school, as trades were taught back then, and she delved into it. Today, she possesses a wealth of unsold product, which her children will inherit. The garments she produces can be repurposed if worn by a woman at a wedding or sold even at a very low price. She describes the current sales as slow to nonexistent because women are leaning towards fashion designers, chasing "trends," and there’s a lack of awareness among the younger generation about the importance of heritage, as she puts it. Some abayas took her a year and a half to make, and she cannot sell them for less than $5,000, but who buys them? What happened to the women she employed and trained? Mari used to assign several women to help her at home, but now due to the halt in demand and sales, they are all unemployed.

As she distances herself from Kesrouan and Metn to compare whether this is only the situation in her area or if it is worse elsewhere, she discovers it is even worse for craftsman Marwan Nasif (South Ain el-Dalab), whose craft, Arabic blacksmithing, requires electricity for the furnace, which is out of reach. The absence of electricity affects his work, so he resorts to using coal and raw materials from abroad or scrap metal from cars. He classifies this craft as one that is at risk of extinction, and it is not a priority for the state, wishing the government would connect them to international associations concerned with crafts, noting the significant role municipalities can play.

Hassan Wahbe, the head of technical artisans in Lebanon, tries to instill positive energy among artisans, rejecting the notion of "complaining." He is awaiting the approval of the presented law, seeing it as a renewal of morale for artisans in Lebanon, as he extends assistance to the "Journey in the Valley" program airing on MTV, which highlights some artisan work in its episodes. This is not all that Wahbe is pursuing; he seeks participation in various exhibitions, praising training courses held by the Ministry of Social Affairs to pass these crafts to future generations. His current focus, after the law, is on securing special items for certain crafts at their headquarters in the Ministry of Industry, which will serve as training grounds, questioning how to transport heavy pottery from the south at a low cost?

Thus, with the cultural and creative industries contributing nearly 5% to Lebanon's GDP and employing 4.5% of the national workforce, according to the study embraced by the "Nous" Association, its director, Mohamed Ayoub, sheds light on the reality that Lebanese crafts are not legally recognized; there is no definition and thus no standards, making it unclear who is a craftsman and who isn’t, leading to a state of confusion. Consequently, artisans are left unprotected, whether culturally, economically, or socially. Based on this data, the association decided to work on protecting the sector, proposing legislation to recognize this “marginalized” group and ensure health and economic protections through a series of measures, including marking everything produced in Lebanon with "Made in Lebanon," imposing high tariffs on any external competition, and establishing factories in Lebanon for extracting or importing raw materials at reduced prices for artisans.

According to the same study, 64.65% of artisans do not export their goods, and 18.25% did in past years, with only 17.19% currently able to do so. All this is attributed to the absence of a formal policy to protect production and the high costs of raw materials and equipment needed for some artisanal activities. This is one indication of the government’s failure to encourage local industry, as he states. Thus, the proposal was made to designate the Ministry of Industry as the sector's overseer, while the Ministry of Economy prevents market flooding. Tourism places production in tourist areas, and culture documents it to prevent its extinction, leaving the Ministry of Social Affairs to incorporate it into the social development plan. So when will the law be passed?